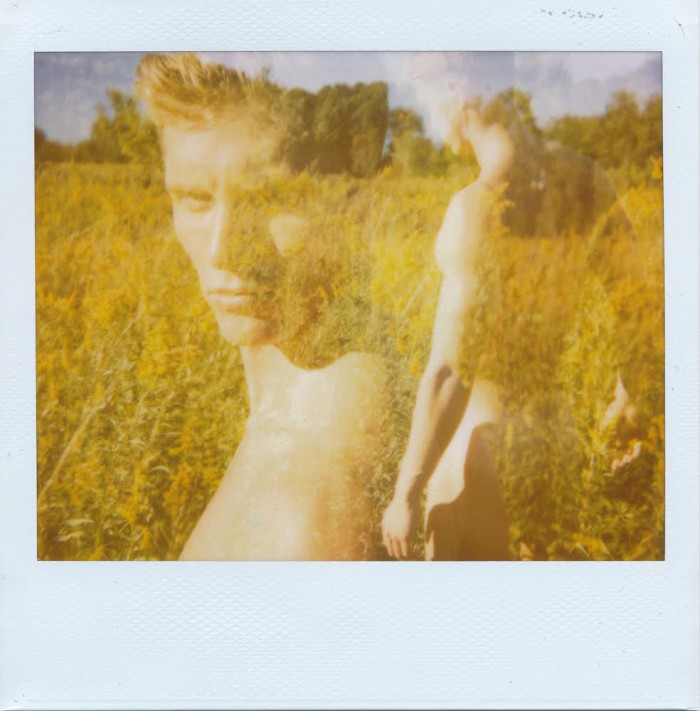

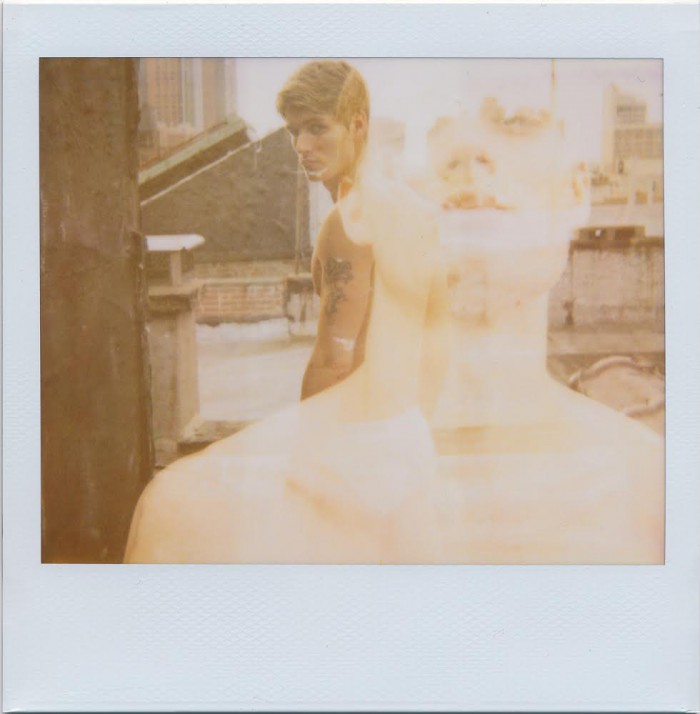

You might know Jeremy Kost (Jed Root) from his photographic collages, from his heavily-trafficked Instagram, or his signature hairstyle, but you definitely don’t know him from his latest work, a lush, powerful selection of multiple-exposure Polaroids now making their first appearance collected in his latest book, Fractured, out later this month. The new images, which blend Kost’s signature masculine nudes with gentle landscapes and harsh neon signage, have been edited down from a nearly four thousand photographs he took over the last three years as part of this secret project, which marks an audacious and bold step forward in his artistic development. The images are explicit, yes, but also intimate and raw, a byproduct of his mix of recognizable names like Garrett Neff (who contributes a personal foreword), Chad White, James Lasky, and Seth Kuhlmann with undiscovered guys cast from Instagram. In an exclusive interview with Models.com, Kost opens up about his aesthetics, his process, and the very personal meaning of his new body of work. (Interview by Jonathan Shia)

Kost will be signing copies of Fractured tomorrow at Bookmarc in New York.

MDC: How did you come up with the idea of doing multiple exposures?

Jeremy Kost: It really happened by mistake. Maybe three years ago, a Polaroid got stuck in the camera in the studio and I made the next frame immediately over it and serendipitously came up with this layered, beautiful image that I was really excited about. I started playing around and figuring out the process and how it worked and how to really push that process. As evident in the collages and different bodies of work that I’ve done, I’m really interested in pushing the Polaroid medium beyond what I’ve been doing from day one. That’s really where it started, and that’s part of the impetus for where it’s gone.

In the end, I’ve always thought about myself as an artist and not a fashion photographer. I never wanted to be a fashion photographer, and I get bored really easily. I can’t shoot in my apartment anymore because I’ve shot it to death, I can’t shoot in a studio because a white wall to me is completely uninteresting. So when that happenstance came about, it opened up a whole new world of possibility for me to reinterpret all those things that had been monotonous before. All these locations that I felt like I’d shot to death, all of a sudden, had a whole new life. It was really exciting, and I felt like people have done multiple-exposed images for years, but I’d never seen it done coherently as a body of work. So for me it felt like I could do something that was really fresh and was uncharted territory in a way.

MDC: Where did the title come from?

JK: Coming up with a title is one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. We went back and forth with this one, and finally I landed on Fractured, which for me represents a lot of different things. First, it’s a really aggressive word, this aggressive, hyper-masculine sense of breaking. In a sense, it goes back to this idea of fractured dreams, fractured memories, fractured desires, fractured hopes, lust, whatever. At three o’clock in the morning, I could be the most inappropriate person on earth, but when I’m working, I’m really working. My hands are to myself, my comments are to myself, I’m hyper professional. As a result, the art really becomes about these fractured desires and this fractured distance. It becomes the closest I’m going to have to that interaction physically, for all intents and purposes. Specifically, it’s really about this identity of a broken facade, these disjointed memories, these disjointed desires, in a very visceral way.

Shayne Davis (IMG)

MDC: How do you hope this new project changes the perceptions people have of you and your work?

JK: I hope that they start to see it as art, and not just pictures of dudes. The male as a subject for me has a lot of personal layering to it, both having been 250 pounds and closeted growing up in Texas, having been in denial to myself until after college, and then continuing to grow as who I am. I still have massive body issues and probably will until the day I die, no matter if I have a body like Garrett’s or I continue to struggle. Hopefully, when people look at this work and read the corresponding text in the book, they can perceive that there’s more to the work than simply what’s on the surface and that there are all these conceptual underpinnings that have nothing to do with the fact that it’s this beautiful naked guy, and that there’s more to it from both a conceptual place and a place of intimacy as a constructed image.

MDC: Speaking of Garrett, why did you pick him to write the foreword?

JK: He and I have known each other for seven years now. We met when we were both were starting out in our various lives, but we have maintained our friendship and have collaborated on a number of projects over the last couple of years. In my first book, the director of the Andy Warhol Museum wrote a text, and then Ladyfag wrote a piece, so I thought it was interesting to have somebody who was writing with a more critical perspective, and then somebody who’s in the work and has a more popular perspective. In the end, Garrett has a pretty decent portion of the book, and he’s also in some of the more personal images. Glenn O’Brien and Franklin Sirmans, who’s a curator at LACMA, also contributed texts, so it was nice to have three straight men writing about the work.

Zach Boyers (Two Management)

MDC: What was the casting process like? What were you looking for in the guys you selected?

JK: When I first started shooting guys in 2001, most of them were dudes whom I met in a bar or wanted to sleep with or whatever, but when I decided to start doing more, I started finding guys through Manhunt and MySpace and all these alternative casting sources. I have a very specific casting æsthetic, it’s very much the Bruce Weber boy next door. As I’ve been working more and more with agencies, I’ve lost some of that thing where it’s just two people making art, without a third person’s opinion or somebody flipping out or any sort of drama. It’s just two people making shit that they’re both excited to make and are both comfortable making. That’s preface to the question, but a lot of the guys come through Instagram. Some contacted me out of nowhere, most of them I contacted, but I really love using Instagram as a casting vehicle, because you can find exceptionally beautiful guys that don’t have the baggage and also, frankly, aren’t show ponies. They’re not trained, so actually you end up getting a more honest image rather than a character, which I think is really interesting too. Everyone that I shoot, we have a conversation about the work and the expectations. I tell them I’m going to make pictures that they can use for Instagram or whatever, but the art, the nude stuff, stays off websites until it’s in a more sophisticated context. I have that same conversation whether you’re with IMG or whether you’re from Instagram. For me, that consistency and transparency is super, super, super important, and what I try to do is lay everything out so that everyone involved can make an educated decision about whether it’s right for them.

MDC: How did the works with the neon signs come about?

JK: I made the first one about a year ago. I snapped a “We Buy Gold” sign on the Lower East Side and then I layered it with a guy I was shooting, thinking, “Maybe this could work.” It was a pure experiment, and it totally worked, and before I knew it, I started looking at text and language and seeing it everywhere. I like the contrast of these guys in these largely rural places with the neon, which is largely urban in context. I think that push and pull is really interesting, and it also asks the question of what it means to take language out of context. Some of it’s meant to be a bit funny, some of it’s meant to be a bit sexual. I’m really excited about them. There’s such a rich history of language in contemporary art, so it sort of has a dialogue with Jack Pierson and Bruce Naumann and Barbara Kruger, some artists that I really respect.

MDC: Some people might classify your work as having a “gay” æsthetic. What is your response to that categorization?

JK: Look, any time there’s a naked guy, it’s considered homoerotic, whether it’s made by a straight man, a woman, or a gay man. Everybody wants to put things in a box so that they can understand them. Fine, I’m not offended by it. If you want to put it in that box, by all means. I certainly don’t make it with that intention. Sure, it’s about the male gaze, there are equal parts desire and lust as well, but there’s a lot more to it about identity, facades, physicality, transformation, all those things that, for me, are equally important, if not more important, than the desire aspect of it. So if that’s how somebody wants to perceive it, I’m not offended. It’s not how I look at it, but it is what it is. So long as somebody’s considering the work, that’s what’s most important to me.